One fantastic feature of JavaScript (compared to say, Python) is that it is possible to bundle your code for packaging; removing everything that is not needed to run your code. We call this “tree-shaking” because the stuff you aren’t using falls out leaving the strongly-attached bits. This reduces the size of your output, whether it’s a NPM module, code to run in a browser, or a NodeJS application.

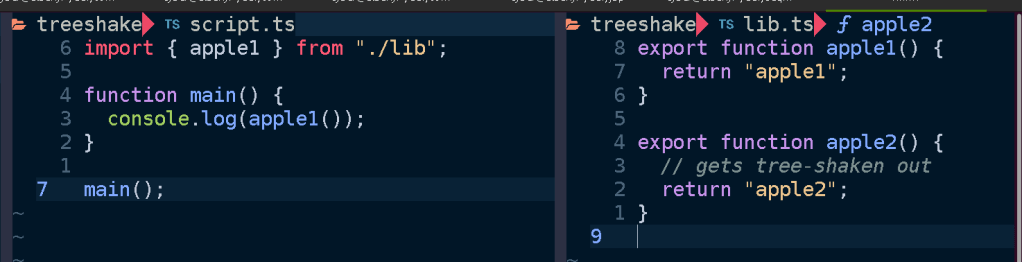

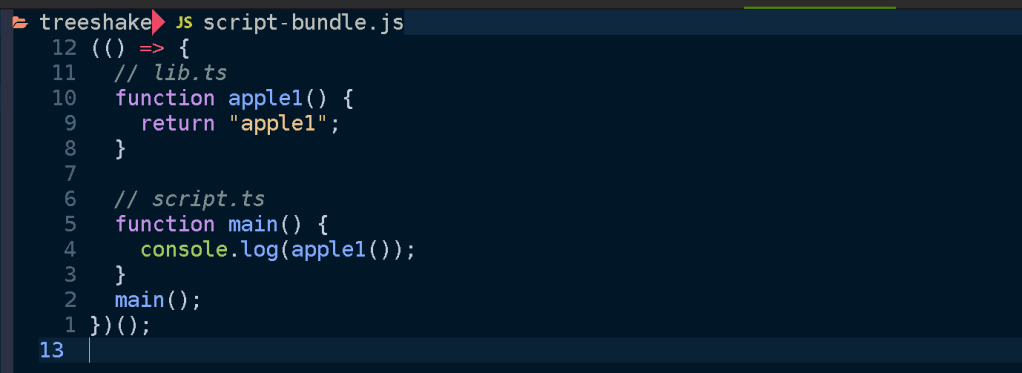

By way of illustration, suppose we have a script that imports a function from a library. Here it calls apple1() from lib.ts:

If we bundle script.ts using esbuild:

esbuild --bundle script.ts > script-bundle.js

Then we get the resulting output:

The main point here being that only apple1 is included in the bundled script. Since we didn’t use apple2 it gets shaken out like an overripe piece of fruit.

Motivation

There are many reasons this is a valuable feature, the main one is performance. Less code means less time spent parsing JavaScript when your code is executed. It means your web app loads faster, your docker image is smaller, your serverless function cold start time is reduced, your NPM module takes up less disk space.

A robust application architecture can be a serverless architecture where your application is composed of discrete functions. These functions can function like an API if you put an API gateway or GraphQL server that invokes the functions for different routes and queries, or can be triggered by messages in queues or files being uploaded to a bucket or as regularly scheduled events. In this setup each function is self-contained, only containing whatever code is needed for its specific functionality and no unrelated code. This is in contrast to a monolith or microservice where the entire application must be loaded up in order to handle a request. No matter how large your project gets, each function remains about the same size.

I build applications using Serverless Stack, which has a terrific developer experience focused on building serverless applications on AWS with TypeScript and CDK in a local development environment. Under the hood it uses esbuild. Let’s peek under the hood.

Mechanics

Conceptually tree-shaking is pretty straightforward; just throw away whatever code our application doesn’t use. However there are a great number of caveats and tricks needed to debug and finesse your bundling.

Tree-shaking is a feature provided by all modern JavaScript bundlers. These include tools like Webpack, Turbopack, esbuild, and rollup. If you ask them to produce a bundle they will do their best to remove unused code. But how do they know what is unused?

The fine details may vary from bundler to bundler and between targets but I’ll give an overview of salient properties and options to be aware of. I’ll use the example of using esbuild to produce node bundles for AWS Lambda but these concepts apply generally to anyone who wants to reduce their bundle size.

Measuring

Before trying to reduce your bundle size you need to look at what’s being bundled, how much space everything takes up, and why. There are a number of tools at our disposal which help visualize and trace the tree-shaking process.

Bundle Buddy

This is one of the best tools for analyzing bundles visually and it has very rich information. You will need to ask your bundler to produce a meta-analysis of the bundling process and run Bundle Buddy on it (it’s all local browser based). It supports webpack, create-react-app, rollup, rome, parcel, and esbuild. For esbuild you specify the --metafile=meta.json option.

When you upload your metafile to Bundle Buddy you will be presented with a great deal of information. Let’s go through what some of it indicates.

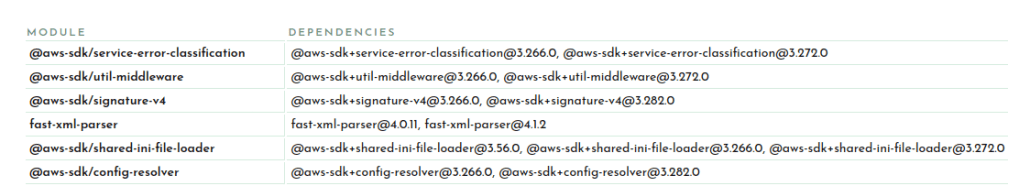

Let’s start with the duplicate modules.

This section lets you know that you have multiple versions of the same package in your bundle. This can be due to your dependencies or your project depending on different versions of a package which cannot be resolved to use the same version for some reason.

Here you can see I have versions 3.266.0 and 3.272 of the AWS SDK and two versions of fast-xml-parser. and The best way to hunt down why different versions may be included is to simply ask your package manager. For example you can ask pnpm:

$ pnpm why fast-xml-parser

dependencies:

@aws-sdk/client-cloudformation 3.266.0

├─┬ @aws-sdk/client-sts 3.266.0

│ └── fast-xml-parser 4.0.11

└── fast-xml-parser 4.0.11

@aws-sdk/client-cloudwatch-logs 3.266.0

└─┬ @aws-sdk/client-sts 3.266.0

└── fast-xml-parser 4.0.11

...

@prisma/migrate 4.12.0

└─┬ mongoose 6.8.1

└─┬ mongodb 4.12.1

└─┬ @aws-sdk/credential-providers 3.282.0

├─┬ @aws-sdk/client-cognito-identity 3.282.0

│ └─┬ @aws-sdk/client-sts 3.282.0

│ └── fast-xml-parser 4.1.2

├─┬ @aws-sdk/client-sts 3.282.0

│ └── fast-xml-parser 4.1.2

└─┬ @aws-sdk/credential-provider-cognito-identity 3.282.0

└─┬ @aws-sdk/client-cognito-identity 3.282.0

└─┬ @aws-sdk/client-sts 3.282.0

└── fast-xml-parser 4.1.2

So if I want to shrink my bundle I need to figure out how to get it so that both @aws-sdk/client-* and @prisma/migrate can agree on a common version to share so that only one copy of fast-xml-parser needs to end up in my bundle. Since this function shouldn’t even be importing @prisma/migrate (and certainly not mongodb) I can use that as a starting point for tracking down an unneeded import which will discuss shortly. Alternatively you can open a PR for one of the dependencies to use a looser version spec (e.g. ^4.0.0) for fast-xml-parser or @aws-sdk/client-sts.

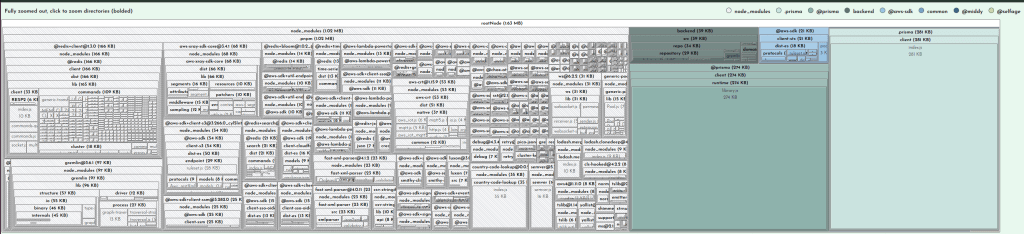

With duplicate modules out of the way, the main meat of the report is the bundled modules. This will usually be broken up into your code and stuff from node_modules:

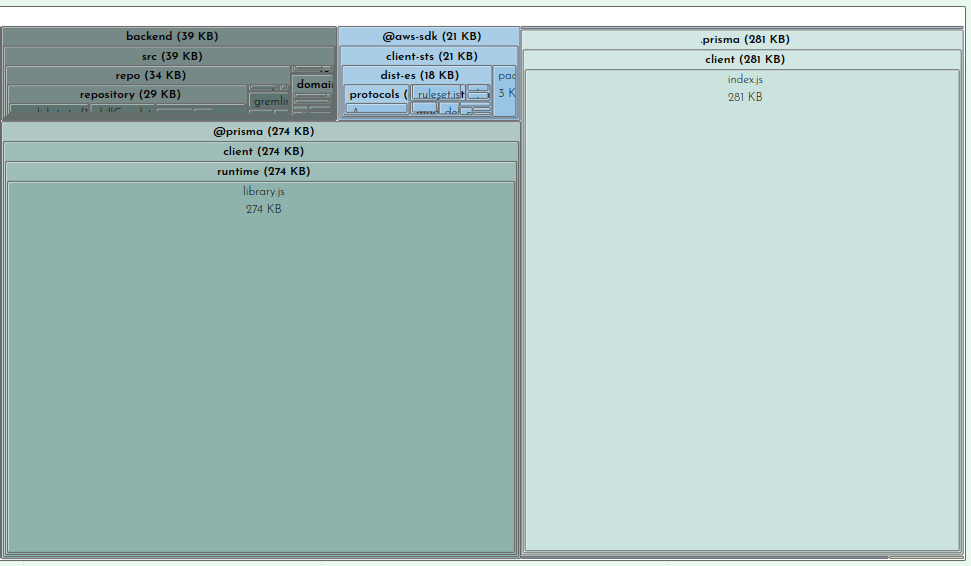

When viewing in Bundle Buddy you can click on any box to zoom in for a closer look. We can see that of the 1.63MB that comprises our bundle, 39K is for my actual function code:

This is interesting but not where we need to focus our efforts.

Clearly the prisma client and runtime are taking up sizable parcels of real-estate. There’s not much you can do about this besides file a ticket on GitHub (as I did here with much of this same information).

But looking at our node_modules we can see at a glance what is taking up the most space:

This is where you can survey what dependencies are not being tree-shaken out. You may have some intuitions about what belongs here, doesn’t belong here, or seems too large. For example in the case of my bundle the two biggest dependencies are on the left there, @redis-client (166KB) and gremlin 97KB). I do use redis as a caching layer for our Neptune graph database, of which gremlin is a client library that one uses to query the database. Because I know my application and this function I know that this function never needs to talk to the graph database so it doesn’t need gremlin. This is another starting point for me to trace why gremlin is being required. We’ll look at that later on when we get into tracing. Also noteworthy is that even though I only use one redis command, the code for handling all redis commands get bundled, adding a cost of 109KB to my bundle.

Finally the last section in the Bundle Buddy readout is a map of what files import other files. You can click in for what looks like a very interesting and useful graph but it seems to be a bit broken. No matter, we can see this same information presented more clearly by esbuild.

esbuild –analyze

Your bundler can also operate in a verbose mode where it tells you WHY certain modules are being included in your bundle. Once you’ve determined what is taking up the most space in your bundle or identified large modules that don’t belong, it may be obvious to you what the problem is and where and how to fix it. Oftentimes it may not be so clear why something is being included. In my example above of including gremlin, I needed to see what was requiring it.

We can ask our friend esbuild:

esbuild --bundle --analyze --analyze=verbose script.ts --outfile=tmp.js 2>&1 | less

The important bit here being the --analyze=verbose flag. This will print out all traces of all imports so the output gets rather large, hence piping it to less. It’s sorted by size so you can start at the top and see why your biggest imports are being included. A couple down from the top I can see what’s pulling in gremlin:

├ node_modules/.pnpm/gremlin@3.6.1/node_modules/gremlin/lib/process/graph-traversal.js ─── 13.1kb ─── 0.7%

│ └ node_modules/.pnpm/gremlin@3.6.1/node_modules/gremlin/index.js

│ └ backend/src/repo/gremlin.ts

│ └ backend/src/repo/repository/skillGraph.ts

│ └ backend/src/repo/repository/skill.ts

│ └ backend/src/repo/repository/vacancy.ts

│ └ backend/src/repo/repository/candidate.ts

│ └ backend/src/api/graphql/candidate/list.ts

This is extremely useful information for tracking down exactly what in your code is telling the bundler to pull in this module. After a quick glance I realized my problem. The file repository/skill.ts contains a SkillRepository class which contains methods for loading a vacancy’s skills which is used by the vacancy repository which is eventually used by my function. Nothing in my function calls the SkillRepository methods which need gremlin, but it does include the SkillRepository class. What I foolishly assumed was that the methods on the class I don’t call will get tree-shaken out. This means that if you import a class, you will be bringing in all possible dependencies any method of that class brings in. Good to know!

@next/bundle-analyzer

This is a colorful but limited tool for showing you what’s being included in your NextJS build. You add it to your next.config.js file and when you do a build it will pop open tabs showing you what’s being bundled in your backend, frontend, and middleware chunks.

Modularize Imports

It was helpful for learning that using top-level Material-UI imports such as import { Button, Dialog } from "@mui/material" will pull in ALL of @mui/material into your bundle. Perhaps this is because NextJS still is stuck on CommonJS, although that is pure speculation on my part.

While you can fix this by assiduously doing import { Button } from "@mui/material/Button" everywhere this is hard to enforce and tedious. There is a NextJS config option to rewrite such imports:

modularizeImports: {

"@mui/material": {

transform: "@mui/material/{{member}}",

},

"@mui/icons-material": {

transform: "@mui/icons-material/{{member}}",

},

},

Webpack Analyzer

Has a spiffy graph of imports and works with Webpack.

Tips and Tricks

CommonJS vs. ESM

One factor that can affect bundling is using CommonJS vs. EcmaScript Modules (ESM). If you’re not familiar with the difference, the TypeScript documentation has a nice summary and the NodeJS package docs are quite informative and comprehensive. But basically CommonJS is the “old, busted” way of defining modules in JavaScript and makes use of things like require() and module.exports, whereas ESM is the “cool, somewhat less busted” way to define modules and their contents using import and export keywords.

Tree-shaking with CommonJS is possible but it is more wooley due to the more procedural format of defining exports from a module whereas ESM exports are more declarative. The esbuild tool is specifically built around ESM, in the docs it says:

This way esbuild will only bundle the parts of your packages that you actually use, which can sometimes be a substantial size savings. Note that esbuild’s tree shaking implementation relies on the use of ECMAScript module

importandexportstatements. It does not work with CommonJS modules. Many packages on npm include both formats and esbuild tries to pick the format that works with tree shaking by default. You can customize which format esbuild picks using the main fields and/or conditions options depending on the package.

So if you’re using esbuild, it won’t even bother trying unless you’re using ESM-style imports and exports in your code and your dependencies. If you’re still typing require then you are a bad person and this is a fitting punishment for you.

As the documentation highlights, there is a related option called mainFields which affects which version of a package esbuild resolves. There is a complicated system for defining exports in package.json which allows a module to contain multiple versions of itself depending on how it’s being used. It can have one entrypoint if it’s require‘d, a different one if imported, or another if used in a browser.

The upshot is that you may need to tell your bundler explicitly to prefer the ESM (“module“) version of a package instead of the fallback CommonJS version (“main“). With esbuild the option looks something like:

esbuild --main-fields=module,main --bundle script.ts

Setting this will ensure the ESM version is preferred, which may result in improved tree-shaking.

Minification

Tree-shaking and minification are related but distinct optimizations for reducing the size of your bundle. Tree-shaking eliminates dead code, whereas minification rewrites the result to be smaller, for example replacing a function identifier e.g. “frobnicateMajorBazball” with say “a1“.

Usually enabling minification is a simple option in your bundler. This bundle is 2.1MB minified, but 4.5MB without minification:

❯ pnpm exec esbuild --format=esm --target=es2022 --bundle --platform=node --main-fields=module,main backend/src/api/graphql/candidate/list.ts --outfile=tmp.js

tmp.js 4.5mb ⚠️

⚡ Done in 239ms

❯ pnpm exec esbuild --minify --format=esm --target=es2022 --bundle --platform=node --main-fields=module,main backend/src/api/graphql/candidate/list.ts --outfile=tmp-minified.js

tmp-minified.js 2.1mb ⚠️

⚡ Done in 235ms

Side effects

Sometimes you may want to import a module not because it has a symbol your code makes use of but because you want some side-effect to happen as a result of importing it. This may be an import that extends jest matchers, or initializes a library like google analytics, or some initialization that is performed when a file is imported.

Your bundler doesn’t always know what’s safe to remove. If you have:

import './lib/initializeMangoids'

In your source, what should your bundler do with it? Should it keep it or remove it in tree-shaking?

If you’re using Webpack (or terser) it will look for a sideEffects property in a module’s package.json to check if it’s safe to assume that simply importing a file does not do anything magical:

{

"name": "your-project",

"sideEffects": false

}

Code can also be annotated with /*#__PURE__ */ to inform the minifier that this code has no side effects and can be tree-shaken if not referred to by included code.

var Button$1 = /*#__PURE__*/ withAppProvider()(Button);

Read about it in more detail in the Webpack docs.

Externals

Not every package you depend on needs to necessarily be in your bundle. For example in the case of AWS lambda the AWS SDK is included in the runtime. This is a fairly hefty dependency so it can shave some major slices off your bundle if you leave it out. This is done with the external flag:

❯ pnpm exec esbuild --minify --format=esm --target=es2022 --bundle --platform=node --main-fields=module,main backend/src/api/graphql/candidate/list.ts --outfile=tmp-minified.js

tmp-minified.js 2.1mb

❯ pnpm exec --external:aws-sdk --minify --format=esm --target=es2022 --bundle --platform=node --main-fields=module,main backend/src/api/graphql/candidate/list.ts --outfile=tmp-minified.js

tmp-minified.js 1.8mb

One thing worth noting here is that there are different versions of packages depending on your runtime language and version. Node 18 contains the AWS v3 SDK (--external:@aws-sdk/) whereas previous versions contain the v2 SDK (--external:aws-sdk). Such details may be hidden from you if using the NodejsFunction CDK construct or SST Function construct.

On the CDK slack it was recommended to me to always bundle the AWS SDK in your function because you may be developing against a different version than what is available in the runtime. Or you can pin your package.json to use the exact version in the runtime.

Another reason to use externals is if you are using a layer. You can tell your bundler that the dependency is already available in the layer so it’s not needed to bundle it. I use this for prisma and puppeteer.

Performance Impacts

For web pages the performance impacts are instantly noticeable with a smaller bundle size. Your page will load faster both over the network and in terms of script parsing and execution time.

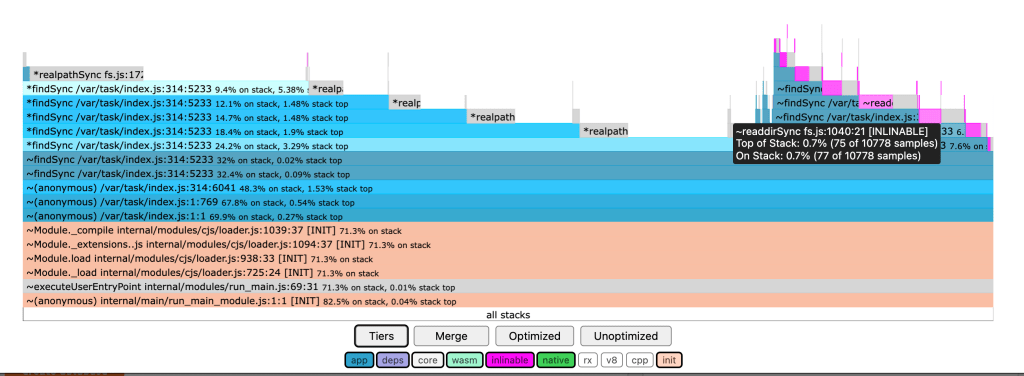

Another way to get an idea of what your node bundle is actually doing at startup is to profile it. I really like the 0x tool which can run a node script and give you a flame graph of where CPU time is spent. This can be an informative visualization and let you dig into what is being called when your script runs:

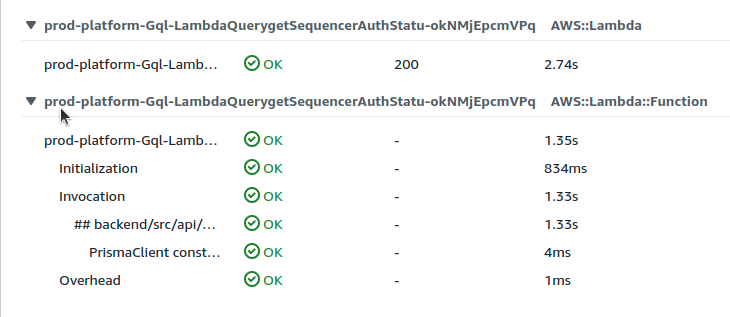

For serverless applications you can inspect the cold start (“initialization”) time for your function on your cloud platform. I use the AWS X-Ray tracing tool. Compare before and after some aggressive bundle size optimizations:

The cold-start time went from 2.74s to 1.60s. Not too bad.